India is charting an unprecedented path in the global AI governance landscape, proposing what could become the world’s first mandatory royalty framework for AI training data. The December 2025 working paper from the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) has ignited a fierce debate that cuts to the heart of value creation in the AI age: who should benefit when machines learn from human creativity?

At stake is not merely a technical question of licensing mechanics, but a fundamental reckoning about algorithmic sovereignty, economic justice for creators, and India’s positioning in the global AI race. The proposals—and the vociferous pushback from NASSCOM and Big Tech—reveal competing visions of how innovation should be balanced against the rights of those whose intellectual labor fuels it.

The DPIIT Framework: Mandatory Licensing with Revenue-Linked Compensation

The DPIIT committee’s hybrid model represents a deliberate departure from both the permissive “fair use” approach common in the United States and the opt-out mechanisms favored in the European Union. Under this framework, AI developers would receive automatic blanket licenses to train models on any lawfully accessed copyrighted content—but with a critical caveat: they cannot commercialize those models without paying statutory royalties.

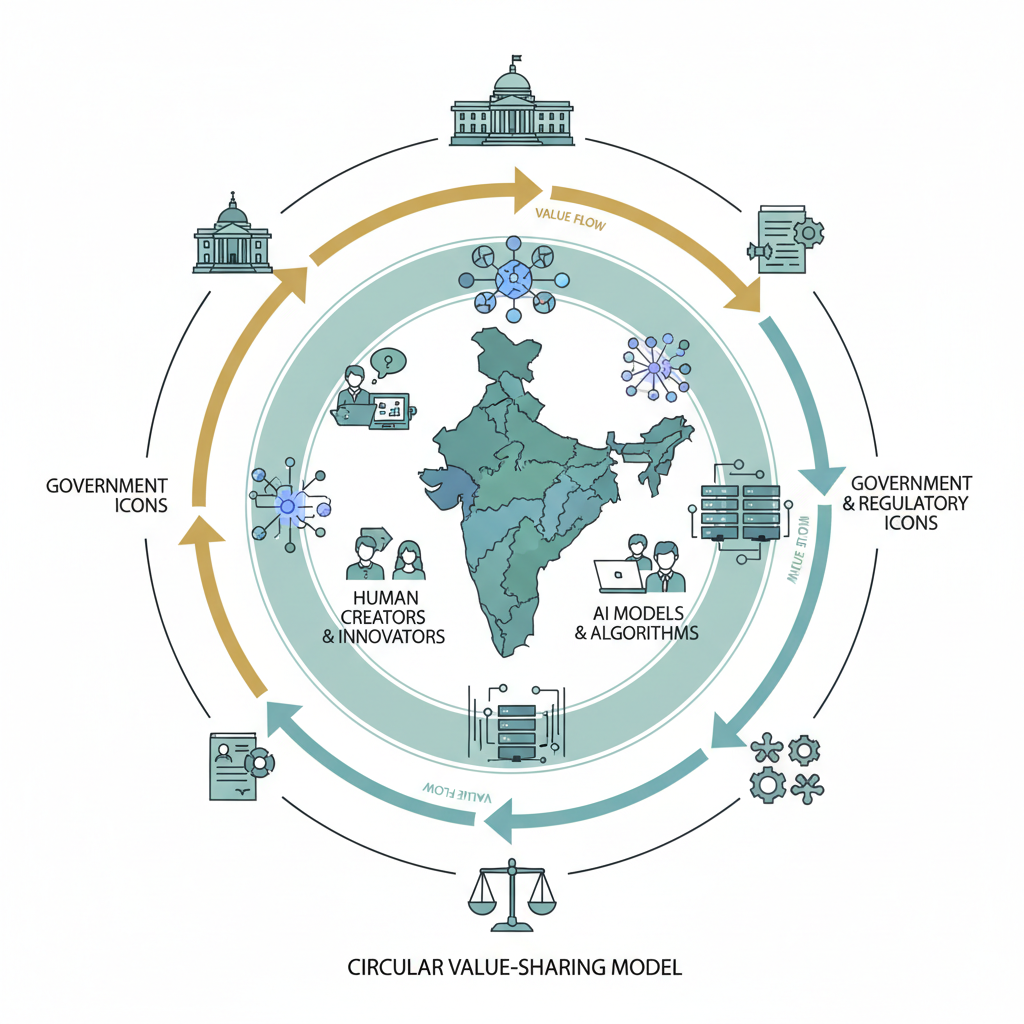

The architecture is designed around three core mechanisms. First, a centralized Copyright Royalties Collective for AI Training (CRCAT) would function as a government-designated non-profit entity collecting and distributing royalties. Second, royalty rates would be set not through market negotiation but by a government-appointed committee, calculated as a flat percentage of the AI system’s global gross revenue. Third, and most controversial, the framework would apply retroactively, requiring companies to compensate creators for data already ingested into existing models.

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) has endorsed this approach, specifically recommending that CRCAT establish minimum revenue thresholds to shield early-stage startups from immediate compliance burdens while ensuring that commercially successful AI systems share returns with rights holders. This threshold mechanism acknowledges a critical tension: the need to foster indigenous AI innovation while preventing the systematic extraction of creative value without compensation.

The philosophical foundation of the DPIIT position rests on a compelling premise: permitting AI developers to freely use copyrighted works without compensation would “undermine incentives for human creativity and could result in the long-term underproduction of human-generated content”. This isn’t merely about fairness to existing creators—it’s about sustaining the ecosystem that generates the very data AI systems depend upon. The committee explicitly rejected “zero-price license” models for this reason, viewing them as fundamentally unsustainable.

The NASSCOM Dissent: Text and Data Mining with Safeguarded Opt-Outs

NASSCOM’s 24-page formal dissent—included in the working paper only after the industry body insisted on full disclosure rather than a mere summary—presents a starkly different vision. The IT industry’s position advocates for Text and Data Mining (TDM) exceptions that would permit AI training on legally accessed content, modeled after frameworks already operational in the European Union, Japan, and Singapore.

The NASSCOM proposal centers on two key safeguards that would replace mandatory licensing. First, creators could implement machine-readable opt-outs for publicly accessible online content, using technical signals like robots.txt protocols or metadata to indicate that their work should not be used for training. Second, for content that isn’t publicly accessible, rights holders could reserve their work through explicit contractual or licensing terms.

The technical and economic objections NASSCOM raises are substantial. Large language models do not store copyrighted content in its original form but convert text into numerical tokens processed probabilistically, making attribution and tracking exceptionally difficult. As one person associated with NASSCOM explained, “What exists inside the model are numbers, not words,” with outputs varying with each prompt. This fundamental characteristic of how neural networks function raises serious questions about enforcement: how can royalties be fairly distributed when the relationship between training data and model output is mathematically opaque?

The economic argument is equally pointed. Token prices for general-purpose AI models like ChatGPT have dropped by 95% since 2023 due to commoditization, and most GPT providers remain unprofitable. In this context, NASSCOM contends, mandatory royalties constitute a “tax on innovation” that could make AI development prohibitively expensive in India, particularly for startups operating with “limited capital, lean teams, and short runways”. The concern is that even modest licensing obligations could “eclipse operational budgets” when revenue is irregular or non-existent.

Big Tech companies have additional concerns about the framework’s legal and competitive implications. They argue that mandatory blanket licensing will expose developers to prolonged legal battles while making India’s regulatory environment significantly more restrictive than competing jurisdictions. The fact that the AI Governance Framework released in November 2025 by the Principal Scientific Advisor’s sub-committee explicitly called for “a balanced approach, which enables Text and Data Mining… while protecting the rights of copyright holders” adds another layer of policy inconsistency.

A Nuanced Take: Beyond Binary Choices

The DPIIT-NASSCOM debate presents what appears to be an irreconcilable conflict, but the most productive path forward likely requires transcending this binary framing. Both positions contain legitimate concerns and overlook critical dimensions of the problem.

The Creator’s Dilemma and Power Asymmetries

The DPIIT framework’s most compelling insight is its recognition of profound power asymmetries in the AI value chain. Individual creators, independent journalists, regional language content producers, and artists in the unorganized sector have negligible bargaining power against multinational AI corporations with market capitalizations exceeding the GDP of many nations. A purely voluntary licensing regime or opt-out mechanism, while theoretically preserving creator autonomy, functions in practice as a take-it-or-leave-it proposition for most rights holders.

The retroactive royalty provision, while administratively complex, addresses a fundamental justice question: AI models already commercialized have extracted enormous value from copyrighted works without compensation. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta have already trained models on decades of human creative output. Allowing this historical extraction to remain uncompensated essentially legitimizes what critics call “the largest intellectual property theft in human history.”

However, the DPIIT framework’s mandatory nature—where copyright holders “cannot withhold their works from AI training” once the blanket license is issued—does eliminate a fundamental property right: the right to exclude. This compulsory licensing approach, while precedented in music and other domains, represents a significant philosophical shift. The working paper acknowledges this tradeoff but argues it’s necessary to prevent AI bias through enabling “more representative and diverse training datasets”. Yet this reasoning is contestable: mandating inclusion doesn’t ensure quality representation, and it’s unclear why reducing AI bias should require overriding creator consent rather than incentivizing voluntary data sharing.

The Innovation Imperative and Competitive Dynamics

NASSCOM’s concerns about compliance burdens and India’s competitive positioning merit serious attention. The AI race is genuinely global, with substantial first-mover advantages accruing to jurisdictions that can deploy models at scale. If India’s regulatory framework increases costs by even 10-15% compared to training models in jurisdictions with TDM exceptions, capital and talent will flow elsewhere. This isn’t hypothetical—Google, Meta, and Microsoft already operate research labs across multiple countries, optimizing for regulatory arbitrage.

The startup ecosystem concern is particularly acute for India, where nascent AI companies lack the compliance infrastructure and legal teams that Big Tech can deploy. MeitY’s proposed revenue threshold mechanism partially addresses this by exempting pre-commercial models, but it creates a new challenge: how do you define when an AI system becomes “commercial”? Is it first revenue dollar, first profit, or when revenue exceeds a specified threshold? These definitions will determine whether Indian AI startups face gatekeeping hurdles or genuine developmental support.

However, NASSCOM’s position understates the sustainability challenge. If AI training operates on a zero-price license model, the economic incentive structure for high-quality content creation deteriorates over time. News organizations, which have already seen dramatic revenue declines due to platform aggregation, face additional pressure if their journalism becomes free training data for AI systems that then compete with them for user attention and advertising revenue. The New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI isn’t merely about past extraction—it’s about future viability.

The Attribution Problem and Technical Realities

The technical challenge that NASSCOM highlights—that LLMs store mathematical representations rather than original content—is real but doesn’t necessarily invalidate compensation frameworks. Copyright law has long managed situations where the relationship between input and output is non-linear. Derivative works, adaptations, and transformative uses all involve complex determinations about the extent of original content in new creations.

The solution likely requires moving beyond use-based attribution toward contribution-based compensation models. Rather than attempting to trace which specific training examples influenced which specific outputs—a potentially impossible technical task—the framework could distribute royalties based on proportional dataset composition disclosed by developers. The DPIIT proposal’s requirement that AI developers submit “AI Training Data Disclosure Forms” providing detailed summaries of datasets used represents a pragmatic approach to this challenge.

This disclosure-based distribution isn’t perfect, it rewards volume of training data rather than impact on model performance—but it’s administrable. More sophisticated approaches might weigh different data types based on empirical research about their relative value in model training, but such approaches would require technical expertise and continuous updating as architecture evolve.

The concern about developers reducing traceability by “adding noise to models” to evade enforcement is more troubling. Any compensation framework requires compliance mechanisms, and if deliberately obfuscating training data becomes standard practice, the entire system collapses. This argues for transparency requirements backed by meaningful penalties—not merely for using copyrighted data, but for failing to accurately disclose dataset composition.

The Jurisdictional Question and Extraterritorial Enforcement

One dimension underexplored in both the DPIIT and NASSCOM positions is enforcement across borders. The DPIIT framework proposes calculating royalties as a percentage of “global gross revenue” generated by commercialized AI systems. But how does India compel a U.S.-based or Chinese AI company to share global revenue data and remit royalties?

The most plausible mechanism is conditioning market access on compliance: AI companies that want to serve Indian users would need to register with CRCAT, disclose training data, and pay royalties. This creates leverage, as India’s 1.4 billion people represent a market no major AI player can ignore. However, it also risks fragmentation—if different countries adopt incompatible frameworks, AI companies may geo-fence their services or operate differential models by jurisdiction, reducing global interoperability.

India’s approach could be more effective if coordinated with other large markets. If the EU, India, and a handful of other significant jurisdictions adopted compatible frameworks—even if not identical—the compliance burden for global AI companies would shift from prohibitive to manageable. The DPIIT working paper’s invitation for public comment represents an opportunity for international coordination before finalization.

Toward a Synthesis: Graduated, Adaptive Governance

Rather than choosing between DPIIT’s mandatory licensing and NASSCOM’s TDM exemptions, a more sophisticated framework might incorporate elements of both through graduated, adaptive governance.

Tiered Opt-Out Mechanisms: Instead of eliminating opt-out rights entirely, the framework could implement a tiered system. Creators with substantial resources (major publishers, film studios, music labels) could exercise machine-readable opt-outs and negotiate direct licensing deals if they prefer. Individual creators and those in the unorganized sector would be automatically enrolled in the CRCAT system, receiving blanket license payments without needing to actively register or police usage. This preserves autonomy for those who want it while providing passive protection for those who lack resources to negotiate individually.

Progressive Revenue Sharing: Rather than a flat royalty rate across all AI systems, rates could scale with commercial success and market position. Early-stage models below specified revenue thresholds could operate under TDM-style exemptions, as MeitY suggested. As models achieve commercial scale, royalty obligations would phase in progressively. Dominant models with market-leading revenues could face higher rates, reflecting both their greater ability to pay and their disproportionate impact on the content ecosystem.

Dynamic Rate-Setting with Industry Participation: Instead of purely government-appointed committees setting rates, the framework could establish multi-stakeholder governance where creators, AI developers, and independent experts jointly determine royalty percentages through transparent processes. These rates should be subject to periodic review based on empirical evidence about AI profitability, content creation economics, and dataset value. Fixed rates determined in 2026 will likely be inappropriate for the AI landscape of 2030.

Strengthened Transparency with Privacy Safeguards: AI developers should be required to disclose detailed training data composition, but such disclosures could be provided to CRCAT under confidential terms rather than publicly released, protecting proprietary information while enabling fair distribution. Regular audits—potentially conducted by neutral third parties—could verify disclosure accuracy without exposing competitive intelligence.

Support for Deliberate Data Contribution: Rather than treating all copyrighted content as passively available for scraping, the framework could create incentive mechanisms for active data contribution. Creators who deliberately make high-quality, structured datasets available for AI training could receive premium compensation rates compared to web-scraped content. This would improve dataset quality while rewarding those who actively participate in AI development.

The Broader Stakes: Algorithmic Sovereignty and Economic Justice

Ultimately, India’s decision about AI copyright compensation is inseparable from larger questions about algorithmic sovereignty and the future of creative labor. If AI systems trained on the collective intellectual output of human civilization generate returns measured in trillions of dollars, who should capture that value?

The DPIIT framework implicitly argues that creators deserve a share because their work made the AI possible. NASSCOM implicitly argues that AI developers deserve maximal freedom because innovation generates broader social value that transcends individual copyright claims. Both positions contain truth, but neither fully captures the complexity.

The most defensible position recognizes AI as genuinely transformative technology deserving supportive policy—while also acknowledging that transformation built on the uncompensated expropriation of creative labor is both ethically problematic and economically unsustainable. The goal should not be to maximize AI developer profits or to maximize creator revenues in isolation, but to sustain a healthy ecosystem where both human creativity and machine intelligence can flourish.

India’s experiment—if implemented thoughtfully, with continued iteration based on evidence rather than ideology—could model how large democracies balance innovation with justice in the age of artificial intelligence. The alternative is allowing the current unsustainable status quo to persist until litigation or market collapse forces a chaotic reckoning.

The consultation period extended to February 6, 2026, represents not an inconvenient delay but an essential opportunity. Both DPIIT and NASSCOM should approach this next phase not as a zero-sum battle to be won, but as a collaborative design challenge: how do we build systems that make AI training economically viable while ensuring that the humans whose creativity makes it possible can continue to create? Getting this wrong will harm India’s AI ambitions. Getting it right could establish the country as a leader not just in AI deployment, but in AI governance that works for everyone in the value chain.